reading time 2.30 minutes

So people died here then sir?

It was a cold, dry and brisk October morning when I took 60 GCSE students to the “darkest place” on earth: Auschwitz.

As we were guided around the site and having been to Auschwitz a couple of times, I decided to look carefully at the students experience of this visit and watch them as they took in their surroundings.

It is easy to take their potentially passive nature as a sign of real in-depth understanding of Auschwitz and all its facets. It was a challenging school and they were respectful, quiet and listening. But actually did they get it? Did they understanding the wider picture?

This was particularly apparent when heading towards the exit in Auschwitz-Birkenau as a student approached me to confirm “so people died here then sir?”.

For an accompanying teacher, they were really taken aback by the fact this normally disengaged student had “got it” and how “engaged” they were. However, the hours of work put into this trip and it’s true educational value started to fade away upon hearing this question… these students had been to Auschwitz, but had they really understood the complexities I had imagined?

So I went back to the drawing board and decided to investigate how we could make these field trips more effective. Following my own visit, I was lucky enough to attend the “Lessons from Auschwitz” programme run by the Holocaust Educational Trust and also the First World War Centenary Battlefield Tours Programme. These programmes were brilliant in their production, execution and focus on teaching and learning. I watched as students engaged with their environment, bringing in their pre-study work and was amazed at the comprehension of these visits in the post-visit brief.

Students really did get it! And so I began to look at what I could do in school to ensure our visits became a meaningful learning experience for the students.

So a Masters’ project later, looking specifically at Teacher perception of field trips, highlighted some major concerns and misconceptions.

- Trips are primarily for student-teacher or student-student relationship development, rather than education.

- Trips have a huge administrative burden for teachers in terms of disruption, cost, staffing, planning and time.

- Teachers desired improvements in more centralised planning/support given

- Teachers saw field trips as very important and very effective

This study also looked to explore the reasons behind such perceptions and found:

- Teachers have very limited field trip or educational visits pedagogy

- Teachers have very limited field trip CPD (other than the administrative side to field trips)

One finding particularly stood out. The idea that trips are primarily for student-teacher or student-student relationship, or as a teacher referred to in the study, “a jolly”.

This was a surprising and alarming attitude for a significant number of teachers to hold. If we perceive the main benefit to be anything other than learning, this has a significant impact on field trips as a whole. We then don’t value the CPD or pedagogy (however limited) surrounding such an area and it means that the field trips themselves become an additional extra which eventually will dwindle as we give way to more content heavy curriculum and more rigorous assessments.

However, ‘terrific trips’ are the answer to the problems faced! Research recognises the value of field trips as an academic endeavour and it is time that we, as teachers, approached it as such.

So what can we do to make our trips meaningful?

- Give trips the educational value they deserve and treat them as such! Yes there is a huge administrative element but delegate and as the teacher focus on the WHY. Why are students on the visit? What do they have to learn? How are we going to get this across to the them?

- Structure, structure and structure!

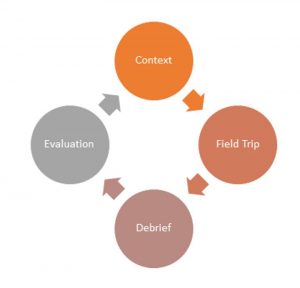

Approach the field trip as a lesson with context sessions so students know what to expect but also debriefs for the students. We should also then look to evaluate the trip in terms of teaching and learning. What could we do better next time for learning? Rather than just looking at a practicalities approach.

I) Context

The context stage consists of presenting contextual information about a given topic and potentially challenging any misconceptions that students may have.

II) Field Trip

At this stage students need to have a contextual understanding of the background to what they are studying.This will make the visit itself more meaningful.

III) Debrief

Thirdly, a debrief session should be provided. After visiting Auschwitz for example, students will often have more questions than answers and having time to digest, discuss and further develop the learning experience is vital. However, this should be conducted away from the original environment. This again leaves opportunity to explore different pedagogical techniques which can best enhance learning.

IV) Evaluation

An evaluation with both students and staff should be had. Whether verbal, written or conducted online we must begin to follow a more positivist approach in applying practical pedagogy.

Go on pre-visit! If we haven’t been there (and this doesn’t include a virtual tour…) how can we really expect the student to get anything meaningful from there? We need to be experts of the environment, in order for us to make the process as smooth as possible for the students; minimal distractions, maximize focus on the learning.

If we can turn field trips from a “jolly” to a purposeful, well-planned learning experience, we can not only enrich students from a cultural perspective, but also help students to deal with the demands of heavy content.